Axel Wilke writes…

In the first half of the 19th century, some of the meadows used by English farmers to graze their cows turned brown. The grass was gone. It wasn’t that the soil was less fertile or that there was less rain than elsewhere. What differentiated the green and brown meadows was ownership. The green meadows had a single owner and the brown meadows were in communal ownership. Those who used communal land knew that there was only capacity to graze a given number of cows. Each user had to use some constraint; let’s say there was enough grass growth for 10 cows each. And if one of them decided to graze 11 or 12 cows instead, it didn’t really do any damage and there was still enough grass growth to satisfy all of the cows.

But the farmer with the greater number of cows had a greater profit. Of course, soon others wanted to have the same added benefit. Before long, it became clear that the situation was unsustainable, with some areas turning brown from overgrazing. But if an individual would respond to the problem by reducing their stocking rate, it quickly became clear that this wouldn’t solve the problem if other farmers responded to this by increasing their cow numbers. As individuals, they could not fix the problem, hence they kept grazing the commonly held meadows. This carried on until the meadows were destroyed. They all knew this would happen but each individual also knew that if they reduced their stocking rate, they would receive a double-punishment as in the end, the meadow would be destroyed anyway.

This situation was first analysed by the British economist William Forster Lloyd in 1833. His essay was soon forgotten and it wasn’t until American ecologist and philosopher Garrett Hardin popularised the problem in 1968 by writing an article about the “tragedy of the commons”.

It is the situation in a shared-resource system where individual users, acting independently according to their own self-interest, behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting or spoiling the shared resource through their collective action. Hardin used overfishing the oceans as an example of the problem.

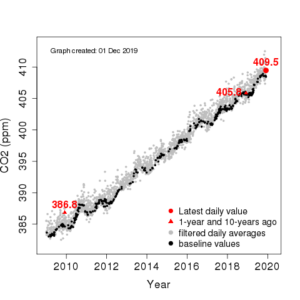

He postulated that free, unlimited access to a resource will result in ruin for everyone. He didn’t write about global warming as in the late 1960s, not many were aware that even the atmosphere is a limited resource. It wasn’t generally thought that it would be possible to fill the atmosphere with too many pollutants. But we have since learned that increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere beyond a safe level gets us into trouble. That safe limit is regarded as 350 parts per million (ppm), and it’s the basis for the name of Bill McKibben’s environmental organisation 350.org. NIWA tells us that today, CO2 concentration at their Baring Head station is 409.5 ppm. Ten years ago, the CO2 measurement came in at 386.8 ppm. Things are pointing in the wrong direction and are progressing at a frightening speed.

How should we, as individuals, respond to the situation?

Is there even any point in doing so, as the tragedy of the commons would apply or our contribution would be so tiny to not make any difference anyway?

Individual action will not make a noticeable difference through imposing personal limitations. Our actions will only start to become truly meaningful when they cause collective change. And this collective change, on a population level, will never be achieved by people taking voluntary measures.

What we as individuals are prepared to take or use less of relies on policy measures set by the government, be it local or central, which limit use across the board. Imposition of limitations by government, while necessary in order to protect the resource from the tragedy of the commons, is not necessarily a popular step. Particularly to those who will lose profit as a result. Even if a significant proportion of us lobby the government to make changes, we can expect significant opposition.

Let’s look at how this might work with vehicle emissions. In Christchurch, this is by far the biggest contributor to greenhouse gases. Vehicle engines have become much more efficient over the last two decades. This has been negated, though, by vehicles rapidly becoming heavier. Add land use changes (urban sprawl) and population growth to the mix and the reason for the rapidly growing transport emissions becomes clear.

Will providing significantly improved public transport turn things around? Will it entice people from their cars? I predict that no, by itself it will not. What is needed is an intervention to limit the individual benefit of taking our cars. This can be achieved by making driving (or parking) more expensive and less convenient. Only local and central government will be able to do that. And they will only impose the measures needed if enough of us say that is what is needed. That is where our individual actions become meaningful; they give governments at various levels the license to act.

There is another reason why individual action is valuable, and that is to do what is morally right. And when you think about it, it’s the same for us as a country.

If New Zealand decided that we will now do what is morally right, it won’t make any real difference across the world as we are such a tiny nation. But by providing leadership, showing other nations what needs doing, and getting other nations on board, we will start to make a difference. And we better get on with it.

Leave a Reply