If you’re like me, you have been staring at the TV with your mouth open as the country of Afghanistan tears itself apart. I remember my father saying that when he fought in the Second World War with the Americans in the Pacific that they were hazardous allies. His observation was that they had little regard for people, or equipment. It seemed to him that it all came too easy, and he found them wasteful.

I was thinking of Dad when I witnessed scenes like this. Vietnam the second.

Here is the writing of a recently retired Judge in USA who arrived as a Vietnamese refugee when the Americans pulled out of Vietnam:

When my family escaped from Saigon, we took little more than the clothes on our backs. The first morning I woke up in Arlington, I took a stroll in the new neighborhood. I was struck by the scenes of people heading to work, going about their business in peace and an orderly way.

I savored the concept of equality at a McDonald’s restaurant where everyone, rich or poor, would receive the same burger and fries after paying the same amount, then about 89 cents. To me, it was and remains what I would call “McDonald’s equal treatment.”

We moved about 12 times, from the East Coast, to the Midwest, to the West Coast. In the United States, I have been, almost without transition from my last legal staff position in Saigon, a dishwasher, a shoe repairer, a newspaper delivery person, a French teacher, a clerk. I would take any jobs available, accept any shifts, including a position walking the beans and detasseling corn under the scorching summer heat in Iowa. I returned to law school and eventually became an immigration judge in San Francisco. My story simply was the path taken by successive waves of immigrants before me.

The United States did not win the war against the Taliban. But now is when the American people can step in and provide the Afghan refugees a haven whereby they can join “we the people” to “form a more perfect Union” for themselves, their children, and their grandchildren.

There will be much analysis of whether Biden got it right or wrong. Whether Trump had cocked up, or not.

People are responding in a very personal way. Here is what Rinith Taing, a journalist, researcher, and poet, wrote:

“Dear Mr Biden,

I am very disappointed in you for repeating another historical scrouge.

Fifty-one years ago, President Gerald Ford ordered for the withdrawal of American troop from Cambodia, leaving our country to the terrible Killing Field built by Khmer Rouge.

And today, you left Afghanistan and her people to the Taliban. I regret for having thought that you would bring real changes to the world. And now, I know, Mr President, that you are just another historical scumbag.”

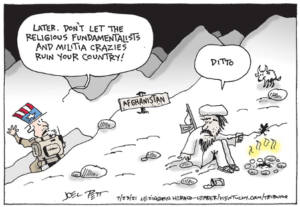

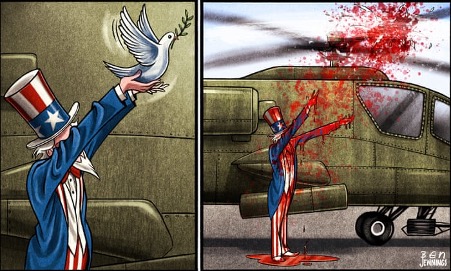

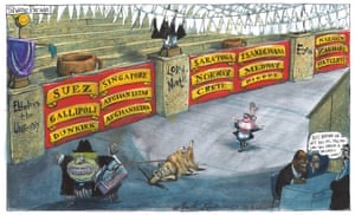

Cartoonists have had a field day.

Then there are stories like this one where a young female journalist describes the panic and fear of being forced into hiding as cities across Afghanistan fall. This article was reported recently by Humanity United

‘Please pray for me’: female reporter being hunted by the Taliban tells her story

Two days ago, I had to flee my home and life in the north of Afghanistan after the Taliban took my city. I am still on the run and there is no safe place for me to go.

Last week I was a news journalist. Today I can’t write under my own name or say where I am from or where I am. My whole life has been obliterated in just a few days.

I am so scared, and I don’t know what will happen to me. Will I ever go home? Will I see my parents again? Where will I go? The highway is blocked in both directions. How will I survive?

My decision to leave my home and life was not planned. It happened very suddenly. In the past days my whole province has fallen to the Taliban. The only places that the government still controls are the airport and a few police district offices. I’m not safe because I’m a 22-year-old woman and I know that the Taliban are forcing families to give their daughters as wives for their fighters. I’m also not safe because I’m a news journalist and I know the Taliban will come looking for me and all my colleagues.

I’m a 22-year-old woman and I know that the Taliban are forcing families to give their daughters as wives for their fighters

The Taliban are already seeking out people they want to target. At the weekend my manager called me and asked me not to answer any unknown number. He said that we, especially the women, should hide, and escape the city if we could.

As I was packing, I could hear bullets and rockets. Planes and helicopters were flying low over our heads. There was fighting on the streets right outside the house. My uncle offered to help get me to a safe place, so I grabbed my phone and a chadari (the full Afghan burqa) and left. My parents would not leave even though our house was now on the frontline of the battle for the city. As the rocket fire intensified, they pleaded for me to leave because they knew the routes out of the city would soon be shut. So, I left them behind and fled with my uncle. I haven’t spoken to them since as the phones are not working in the city anymore.

Outside the house it was chaos. I was one of the last young women left in my neighbourhood to try to flee. I could see Taliban fighters right outside our house, on the street. They were everywhere. Thank God, I had my chadari, but even then, I was afraid they would stop me or would recognise me. I was trembling as I was walking but trying not to look scared.

Just after we’d left a rocket landed right next to us. I remember screaming and crying, women and children around me were running in every direction. It felt like we were all stuck in a boat and there was a big storm around us.

We managed to get to my uncle’s car and started driving towards his house, which is 30 minutes outside the city. On the way we were stopped at a Taliban checkpoint. It was the most terrifying moment of my life. I was inside my chadari, and they ignored me but interrogated my uncle, asking him where we were going. He said we had been visiting a health centre in the city and were on our way home. Even as they were questioning him, rockets were being fired and landing close to the checkpoint. Finally, they let us go.

On the way we were stopped at a Taliban checkpoint. It was the most terrifying moment of my life

Even when we got to my uncle’s village, it wasn’t safe. His village is under Taliban control and many families are Taliban sympathisers. A few hours after we arrived, we were told some of the neighbours had discovered he was hiding me there and that we had to leave – they said the Taliban knew I’d been taken out the city and if they came to the village and found me there, they’d kill everyone.

We found somewhere else for me to hide, a home of a distant relative. We had to walk for hours, with me still in my chadari, staying away from all the main roads where the Taliban might be. This is where I am now. A rural area where there is nothing. There is no running water or electricity. There is barely any phone signal, and I am cut off from the world.

Here’s how an article by Francis Fukuyama in the Economist viewed USA pulling out of Afghanistan:

The much bigger challenge to America’s global standing is domestic: American society is deeply polarised and has found it difficult to find consensus on virtually anything. This polarisation started over conventional policy issues like taxes and abortion, but since then has metastasised into a bitter fight over cultural identity. The demand for recognition on the part of groups that feel they have been marginalised by elites was something I identified 30 years ago as an Achilles heel of modern democracy. Normally, a big external threat such as a global pandemic should be the occasion for citizens to rally around a common response; the covid-19 crisis served rather to deepen America’s divisions, with social distancing, mask-wearing and now vaccinations being seen not as public-health measures but as political markers.

These conflicts have spread to all aspects of life, from sports to the brands of consumer products that red and blue Americans buy. The civic identity that took pride in America as a multiracial democracy in the post-civil rights era has been replaced by warring narratives over 1619 versus 1776—that is, whether the country is founded on slavery or the fight for freedom. This conflict extends to the separate realities each side believes it sees, realities in which the election in November 2020 was either one of the fairest in American history or else a massive fraud leading to an illegitimate presidency.

Throughout the cold war and into the early 2000s, there was a strong elite consensus in America in favour of maintaining a leadership position in world politics. The grinding and seemingly endless wars in Afghanistan and Iraq soured many Americans not just on difficult places like the Middle East, but international involvement generally.

Polarisation has already damaged America’s global influence, well short of future tests like these. That influence depended on what Joseph Nye, a foreign-policy scholar, labelled “soft power”, that is, the attractiveness of American institutions and society to people around the world. That appeal has been greatly diminished: it is hard for anyone to say that American democratic institutions have been working well in recent years, or that any country should imitate America’s political tribalism and dysfunction. The hallmark of a mature democracy is the ability to carry out peaceful transfers of power following elections, a test the country failed spectacularly on January 6th.

The biggest policy debacle by President Joe Biden’s administration in its seven months in office has been its failure to plan adequately for the rapid collapse of Afghanistan. However unseemly that was, it doesn’t speak to the wisdom of the underlying decision to withdraw from Afghanistan, which may in the end prove to be the right one. Mr Biden has suggested that withdrawal was necessary to focus on meeting the bigger challenges from Russia and China down the road. I hope he is serious about this. Barack Obama was never successful in making a “pivot” to Asia because America remained focused on counterinsurgency in the Middle East. The current administration needs to redeploy both resources and the attention of policymakers from elsewhere to deter geopolitical rivals and to engage with allies.

The United States is not likely to regain its earlier hegemonic status, nor should it aspire to. What it can hope for is to sustain, with like-minded countries, a world order friendly to democratic values. Whether it can do this will depend not on short-term actions in Kabul, but on recovering a sense of national identity and purpose at home.

In the UK the reaction has been similar towards the Government as it has been in USA. Have a listen to a superb speech by Conservative Party MP Tom Tugendhat to the House of Commons on the 18th August 2021 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-politics-58259509.

The Guardian then produced this cartoon.

The words at the bottom of this cartoon are: “before we let you on can you tell us could you drive a delivery van?”

Simon Tisdall said in the Guardian:

The Afghan project failed. The tarnished age of Pax Americana and the “endless military deployments” Biden deplored is thankfully drawing to a close. Nato – discredited, ill-led, and taken for granted – has had its day, too. A more balanced, more respectful US-Europe security relationship is required. Without it, there may be no western alliance left to lead.

How does this affect New Zealand?

I have heard from friends who are in communication with people in Kabul that the Taliban are going from house-to-house murdering people who they feel supported the last Government or people who are another caste. They are doing this as you read this document. We really do have to quickly assess what supportive role we must undertake as a country.

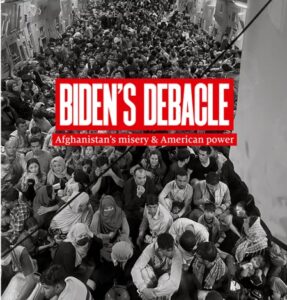

Our defence force behaved in an amazing manner flying to Kabul. Here is a photo of what they were facing. Nobody would want to relace places with these troops having to walk away from desperate people, knowing that there were hundreds of others who they should have been taking.

We have a responsibility as a country to expand our quota of refugees. Abbas will argue this when he speaks next week.

Nicky Hager wrote an article on Afghanistan and ended by saying:

The lesson of the Afghanistan war, like the Vietnam war, and indeed the First World War – for the public and the soldiers – is that we should not have gone in the first place. Was it worth it? No. Should New Zealand have been part of the war? No. Should we have stayed for 20 years? No. Will we learn? That’s up to us.

I thought I would finish this article by quoting Ben Thomas from an article written in Stuff last Thursday:

“The honour of the Crown” is a term that is often used in Treaty settlements. It is something that states-people take seriously. Faced with what is essentially the return of a nightmare for Afghanistan, one from which the West has essentially guaranteed there will be no delivery in the future, it’s hard to see how the honour of a country like New Zealand does not require taking as many refugees as possible

Leave a Reply