I confess that my years and years as an altar boy made me a great admirer of ceremony. So, despite having COVID, I sat down at 7pm on Saturday night to watch the Coronation. The pomp and ceremony were fantastic. I went to bed at 12.30…..

Amongst the many blogs I read is one called “From the other side of History”. I don’t always agree with the author, but he has an interesting view of life. In one last week he wrote about King Charles and his influence on architecture. I have been given long lectures on this topic by Jim Lunday who worked with Charlie at one stage in his life. Jim is a big fan of Charles’ appreciation and understanding of villages and architecture. So, this article interested me: https://edwest.substack.com/p/let-us-call-him-king-charles-the

Cars changed all this, not just by frightening pedestrians off the road and leading to the decline of civic space, but encouraging urban sprawl, which is far less attractive. Suburbanisation meant space and freedom but it also signalled withdrawal from civic life, and the result could be a new form of loneliness. Car dependent suburbs easily lost their amenities and lacked the sort of central points that were vital for healthy communities — shops, pubs, village greens and all the places that lead to serendipitous meetings.

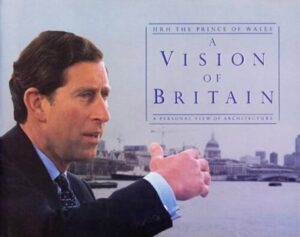

King Charles, as Prince of Wales, has already had a big impact on British architecture, in particular sabotaging attempts by high-profile modernist architects to impose their terrible ideas on the city. Charles was right about modern architecture long before it came to be accepted that much of what was put up in the late 20th century was complete excrement. The Prince was widely mocked, but he knew that in the long term he’d be proven right.

Architecture is hugely influenced by status games, and status competition is driven by insecurity, with new entrants to the upper middle class often the most desperate to adopt the right views. Charles was able to express some incredibly low-status opinions on architecture, perhaps because he was fairly secure about his status (being Prince of Wales and all that).

One of the advantages of monarchs is that they have an interest in caring about posterity in a way that democratic politicians don’t. Elected leaders can’t even think about 11 years into the future, let alone 100. Hereditary rulers know that their grandchildren and great-grandchildren will carry their name and so take the blame and credit for what they did.

King Charles, ignoring the mockery of the establishment and its midwit cultural camp followers, will already give to posterity the towns of Poundbury and South East Faversham; Poundbury is not without its faults, but it presents a real legacy and is far more attractive than most contemporary developments, and his new Cornish development of Nansledan looks excellent.

In contrast, there is barely a single building commissioned by democratic politicians of the past seven decades that will be loved or cherished by our great-grandchildren; many will have been demolished by then. Already the grotesquely overpriced Euston 3 looks almost as ugly as Euston 2, a truly impressive achievement. As Kenneth Clark famously observed in Civilisation, ‘If I had to say which was telling the truth about society, a speech by a minister of housing or the actual buildings put up in his time, I should believe the buildings’ – and what a truth they reveal.

Nothing would better suit the new King’s role than to build a new generation of towns and suburbs, and provide much needed housing for his young subjects. King Charles has a very limited role within the constitution, but his potential legacy is enormous if he wants it — beautiful towns and cities to last the years, living streets that in centuries to come people will want to gaze at and talk about. We need a dozen more Poundburys, a hundred more Nansledans. Build them, Your Majesty! Build them.

Excellent article, which many NZ architects and planners should heed. So much going up today is so ugly, pedestrian , and so disappointing.