There was an interesting article in the Washington Post about art. Here is a small part of what it said:

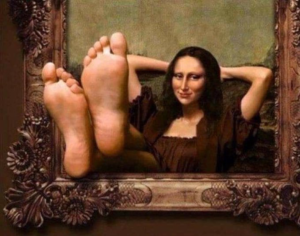

So, what is the art doing now, during this long hiatus that may keep the Mona Lisa with her feet up for months? The reclining Mona Lisa meme suggests that we think (or hope) that the art is resting up, getting ready for us again, preparing to reengage us when we can get back to public life and the museums are open once more.

Another way to ask this is, what is happening with aura now that almost the whole world is shut off from the art itself, able to access only reproductions, and mainly digital ones? Is the aura regathering? Is it re-accumulating in the art, like the fictional dolphins and swans returning to Venice? Is it getting ready for our return to a shriven world, sadder, smaller but somehow purer than before?

Those are fantasies, and powerful ones. But the reality is this: We won’t return to the same Mona Lisa, or any other work that existed before the coronavirus pandemic. We can’t even begin to understand all the ways it will be different. Travel and tourism may return, but they may no longer be accessible at the same scale, and to as wide an audience. There will probably be new inequalities and hierarchies in the access to art. The exchange of private tours for promised donations, deeply embedded in the economy of many museums before the coronavirus, may be explicitly monetized: Pay us up front to see art without the public and its pathogens.

If thousands die and millions are unemployed, art will be for many people more local, no longer about a trip to Paris and a day at the Louvre, and more a matter of finding something sustaining near to hand, as cheaply as possible. If social distancing becomes embedded in our behaviour, the psychology of our great, big-city museums will be different, too. It may be a long time until museums feel comfortable packing their galleries like they once did. And even then, a quick jostle past an iconic work, thronged with a few hundred fellow art pilgrims, will feel very different than it once did.

The greatest difference will be at the personal level. Art almost always feels different to us after a great shock, after a health scare or major illness, or the death of a loved one. Sometimes things that seemed important feel suddenly insipid, and vice versa. We tend to attribute these changes as much to the work itself as to our own changed condition. We think the painting was only pretending to be good, or hiding its true value, and the change in our perception has something to do with the modesty or wiles of the art work itself.

Perhaps we will return to the world in which great works, like the Mona Lisa, have aura. But it would be better if we didn’t. If we could transfer that fantasy about art — that there is something magical in its presence, that it is somehow human, like us, with emotions and agency — to actual people, we would live in a far better world.

We might then put these great works in a new category, no longer relics of a sacred past, but harbingers of a new, humanist future. We would thank them for having taught us to invest other humans with the same value we vested in them, and then, perhaps, the Mona Lisa could really put her feet up and indulge a satisfied smile.

Leave a Reply