We had an interesting discussion from the perspective of residents’ associations and a planner. We had Tony Simons from the combined residents’ association chair and Jim Lunday who is a planner. There was much debate about the need for housing and just where it should be placed.

We need a serious discussion as a city on how we intensify. It needs to be undertaken in a measured and sensitive manner. Those of us of the baby boomer generation were given a clear break to purchase houses by earlier generations. Then we pulled up the ladder for those who followed us and it’s up to us of this generation to lead the debate to find ways for our kids and grandchildren to own their own houses, or to have access to affordable rental housing.

Watch this session on facebook here and questions here

I reflect on the beautiful home we live in. It replaced our home of 39 years which was destroyed by the earthquakes. We had insurance. Think about those who cannot afford their insurance because of all the payouts the insurance industry has had to pay out around NZ. Reflect on those with mortgages which require them to have the insurance they can’t afford. They will be struggling.

I also ponder on those who accepted a full insurance payout and then sold their damaged homes and kept the insurance payout as well. Many young people bought these homes which had been shabbily rebuilt with no council inspection and are now finding out that they have a dog which will continue costing them forever. The insurance payout was part of a contract uberrimae fidei. That means “of the utmost good faith”. The money should have stayed with the house. Many people did the ethical thing. Many didn’t.

I was visiting Burwood hospital this weekend and was horrified at land, which is marginally stable at best, but where we grew our food for at least a century, is now covered in houses. This is precisely what we don’t need. I expect our council to employ decent planners who can stabilise the debate on housing and raise it to the how-can-we-retain-a decent-inclusive-society-and-not-expand- exponentially.

This movement into our food growing areas is totally unacceptable. The developer swoops in and undertakes the development makes their profit and leaves any subsequent issues to the local authorities. It’s not the answer. We must intensify. That requires decent discussions which rise above self interest by our generation and plan for and embrace future generation’s needs.

After our meeting I was informed that the CCC papers for deliberation this week have a recommendation to halt PC14. Here’s what the combined residents’ group has written to the Council:

We note council officers are now recommending a pause in the PC14 hearings process; to be discussed and voted on at the next CCC meeting on December 6th [Item 19]. We strongly urge you and all councillors to vote to support the recommendation.

Citizens groups on Christchurch have been advocating for some time for PC14 to be stopped. Our letter to former council CE, Dawn Baxendale (Sept 18th) asked for a pause and pointed out the significant risk associated with continuing, given we all knew any change of government would result in game-changing legislative changes. Now there is no doubt.

Proceeding with PC14 threatens to become an even more expensive exercise for unknown benefit. Also, continuing the process, when we know the rules are changing, can only create confusion for those submitters yet to present. Essentially submitters, including those yet to present, have had to frame their submissions around the fact of mandatory MDRS and the higher density intensification proposals that accompanied that requirement.

Now that MDRS is to be made optional, the responsible course of action is to stop the process and consider whether or not a new consultation needs to start at a later date when there is legislative certainty. We are thankful council officers agree.

A pause is also justified because PC14, and everything that led up to it, has been rushed (“streamlined”), residents have been poorly supported, major changes have been proposed since notification (without public consultation), and the wider public had no opportunity to submit on those recommended changes.

I understand that the combined resident’s group has been motivated to preserve and protect their existing houses and lifestyles. However, I do not accept at all the argument that we have enough existing houses. The data is clear. We don’t. They must be built and they must be affordable.

Since our meeting on Tuesday night, I have reflected on this challenge by reading several opinion writers and here is what I have found in the last week.

Bernard Hickey, writing in Kaka (which I recommend you subscribe to) wrote:

Baby Boomers who own their own house have been able to leverage their equity to buy investment properties that have been inflated by cheap debt, lax regulation and a tax regime that favours this form of investment. Successive governments have been too scared to move against this market distorting behaviour. The incoming government shows every sign of continuing in this direction and would have been encouraged to do so by political supporters and donors.

National has promised to look after the “squeezed middle” but makes no real mention of those who are being crushed at the bottom. One of the convenient, in-built articles of neoliberal faith is that success is all down to individual effort or personal failure. Poverty is a moral failure and has nothing to do with the failure of the market or the government that is supposed to govern for everyone.

From an article by Aaron Smaile in Newsroom A young, browner future for NZ (newsroom.co.nz)

Plans by Kainga Ora for social housing in Kerikeri in Northland were met with similar outrage, although the language wasn’t quite as hyperbolic. Going by the number of grey heads at the public meetings it was the same Pākehā Baby Boomers who were driving the opposition. The composition of the audience attending the meetings had a similarity to the campaign meetings of National, ACT and NZ First.

In both responses the intention was clear – change didn’t belong in their neighbourhood, and they were going to do everything they could to make sure it stayed that way. The objections might not even mention Māori, but it was and is about exclusion, about protecting something of monetary value. The mere suggestion of the presence of someone not quite like them or public housing or cheaper homes posed a perceived threat to that value.

The generation of Pākehā Baby Boomers has been led to believe that it should be at the centre of political and economic decision-making, largely because it has had the dominant numbers throughout every stage of their lives.

But the dominance of Pākehā Baby Boomers now poses a political and economic problem that can no longer be ignored. This generation is going to start costing the country as it heads into retirement and becomes a heavier burden on the health system. The number of Pākehā coming through from the next generations will not be enough to replace them in numbers or tax revenue as those costs mount up.

He then wrote:

But will the incoming government address the needs of the growing number of Māori, so they get to enjoy the same life choices that Pākehā Baby Boomers have enjoyed throughout their lifetime? More to the point, will the next generation of Māori and Pasifika be in a healthy economic position so the country’s tax revenues can pay for the kind of retirement and healthcare system that Pākehā Baby Boomers are expecting? Or will this government continue to assume that brown people will continue to languish in statistics that show them lagging behind in key social and economic indicators?

One of the people who commented about housing in the last few years has been Don Brash who was Governor of the Reserve Bank from 1988 to 2002. He said people are quick to point out an increase in income inequality over the past 20 years – but New Zealand’s wealth divide has been driven by house prices.

What Brash was effectively saying was that the market had failed, and governments of both sides were unwilling to make structural changes to the legislation and drivers to address it.

In the Kaka it was noted that Brash had identified that there were people locked out of home ownership, he didn’t mention that it was his own generation and cohort that was the voting bloc the politicians were terrified of offending. In the column it was noted:

The problem was actually looking at him in the mirror. If he wanted to name a group that was getting special – or favoured – policy treatment by the government, it wasn’t Māori, it was Pākehā in his age group.

Arthur Grimes, an economist had commented on housing affordability which caused Brash to comment:

“Arthur spelt it out very bluntly but what he was saying was absolutely right – you cannot get affordable housing arithmetically, if you like, without a fall in prices – or wait half a century,” Brash said.

“If you could hold house prices static for half a century and have nominal incomes growing, at say 3 per cent, you might get back to a reasonable relationship over half a century.”

“In the meantime, two generations are locked out of housing.”

Bernard Hickey then looked across the ditch to find what was happening and had happened over there:

Australian business columnist Alan Kohler has written a treatise on how to fix Australia’s housing mess over at Quarterly Review. The problems and solutions are similar to here, although Australia is now more advanced in pursuing a YIMBY formula to beat down the NIMBYs. New South Wales’ new Government announced a massive upzoning for 112,000 extra homes in Sydney earlier this week.

High-priced houses do not create wealth; they redistribute it. And the level of housing wealth is both meaningless and destructive. It’s meaningless because we can’t use the wealth to buy anything else – a yacht or a fast car. We can only buy other expensive houses: sell your house and you have to buy another one, cheaper if you’re downsizing, more expensive if you’re still growing a family. At the end of your life, your children get to use your housing wealth for their own housing, except we’re all living so much longer these days it’s usually too late to be useful.

It’s destructive because of the inequality that results: with so much wealth concentrated in the home, it stays with those who already own a house and within their families. For someone with little or no family housing equity behind them, it’s virtually impossible to break out of the cycle and build new wealth.

As I will argue, it will be impossible to return the price of housing to something less destructive – preferably to what it was when my parents and I bought our first houses – without purging the idea that housing is a means to create wealth as opposed to simply a place to live. Alan Kohler viaQuarterly Review extract.

His diagnosis is frustratingly familiar.

Three main things pushed up demand for housing after 2000: a sharp lift in immigration that increased the number of people needing a place to live; capital gains tax breaks and negative gearing, which represent a $96 billion per year subsidy for buying houses; and federal first home buyer grants, which represent a $1.5 billion direct addition to house prices each year.

As for supply, in 2018, researchers at the RBA figured out that zoning restrictions raised the average price of detached houses by 73 per cent in Sydney, 69 per cent in Melbourne and 29 per cent in Brisbane. For apartments, the figures were 85 per cent in Sydney, 30 per cent in Melbourne and 26 per cent in Brisbane. Those are astonishing numbers, and that’s without including the effect of local government planning decisions, which are, by definition, haphazard and unquantifiable but mostly aimed at keeping local councillors in a job by keeping the existing residents happy by making sure they don’t let in too many new ones. Alan Kohler via Quarterly Review extract.

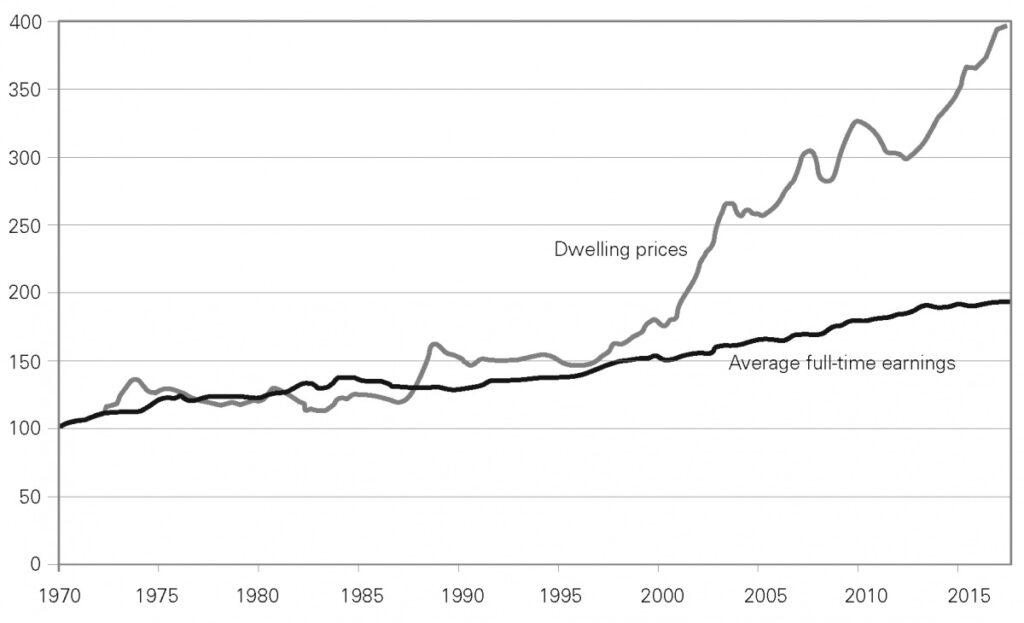

Australian house prices and earnings via Alan Kohler at Quarterly Review

The graph above should provide a clue.?What happened in the 1980s/90 the may have affected housing costs. Oh -that’s right! Classical economic theory gained dominance.

And can someone (preferably an economist, explain to me why, despite having urban planning strategies since the 1970s Christchurch has remained relatively affordable compared to other NZ urban centres.

Regarding intensification- nothing wrong with it- if it is done well. The MDRS was poorly conceived, based on weak assumptions and not needed in Christchurch. No wonder people want to see it gone candy you don’t need to be a NI MIBY to see it that way.

GCP meeting this week includes a recommendation to have more of that serious conversation on housing, and what to do about it (Item 5). Most of the Phase 1 actions for the Joint Housing Action Plan are still to “investigate”, but with commitment from all partners – and linked in with the spatial plan – well I’m hopeful anyway, regardless of the PC14 outcome.

Deputations from the public are very possible, if you have time on Friday morning? Phase 1 looks harmless enough – cost is more staff time than $$$ – but based on the stats we already know about affordability and needed typologies, we’re going to need wholehearted support from all parties for Phase 2 and beyond. The necessity is high, but based on MDRS/PC14 type convos.. the political palatability could dip rather low.

https://greaterchristchurch.org.nz/assets/Documents/greaterchristchurch-/GCP-Meetings/Greater-Christchurch-Partnership-Committee-Agenda-8-December-2023.PDF