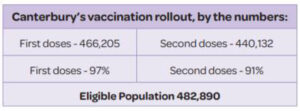

We are doing well as a region when it comes to getting vaccination jabs.

Last week I printed an email I received from one of the Tuesday Club attendees, who now can’t attend in person because he is not vaccinated. I received this reply to his challenges. Here it is:

Your email asked:

Is getting vaccinated “a small burden that contributes significantly to the public good”?

“Could an alternative interpretation of these ‘others’ … be that they questioning (sic) the actual size of the burden that contributes significantly to the public good, the actual size of the public good benefit and the actual value of the good being given up? … conclusions [should be] taking in deep and broad information about this virus, this “vaccine”, one’s own activities and state of health, government controls… the actual risks for people, segmented by state of health …”

Answer:

The references to ‘state of health…” etc here implies that younger, fit and healthy people have little to fear from Covid and so needn’t get vaccinated. I don’t know if this was the intention, but if it was there are flaws in this reasoning:

- In a country that has not suffered significant Covid infections it is easy to underestimate the seriousness of Covid and to think it is only a disease of the old and feeble. I know a number of fit and healthy younger friends abroad who have been seriously ill with Covid. As examples, a dear friend in South America who has never been to hospital, won an international seniors downhill ski race in Europe (she is in her mid-40s) and not long after was hospitalised for a week seriously ill with Covid; a super fit member of my whanau in her 20s who has competed as a national level rower likewise was hospitalised in the UK… Covid is a nasty disease for the unvaccinated. The published data show that in the current NZ delta outbreak people of all ages have been hospitalised (average age: mid-40s).

- Unvaccinated people are more likely to contract the disease and to spread it to others. This is the major factor associated with vaccinating school-age children. Remaining unvaccinated and enhancing the spread of the disease to others are both factors that increase the burden on the healthcare system. The NZ delta outbreak data show that the burden born by the healthcare system is primarily due to unvaccinated people (even though they are a small minority of the population.

So, on that note, let’s come to the most significant public good benefit of getting vaccinated.

Why have governments worldwide, of all political persuasions, curtailed individual freedoms with lockdowns and public health measures, including an emphasis on vaccination?

Of course the primary reason has been (in the absence of effective vaccines) lots of people die prematurely from the disease (the average victim loses more than 5 years of life). However, a more overarching issue is the ability of the healthcare system to cope with large outbreaks when Covid patients overflow the capacity of suitable hospital beds, especially ICU beds. As a country which has systematically under-resourced public health for decades this is a real danger in NZ.

Even healthcare systems with resources beyond anything NZ could ever dream of, like that in Germany, can get overwhelmed. To put this in context, NZ has a few hundred ICU beds and typically about 25 ‘spare’ beds available at any one time. Currently, with an Auckland outbreak controlled in part by vaccination levels and significant social restrictions about a third of those beds are occupied with Covid patients (all, or almost all, unvaccinated). Germany, with a slightly lower vaccination rate (68% vs 72% of total population fully vaccinated) is in the middle of a major outbreak. More than 4,000 of its 22,000 ICU beds are occupied by Covid patients.

This per capita hospitalisation rate would destroy the NZ healthcare system as we know it. When a country’s healthcare system is overwhelmed many people beyond Covid patients die – e.g. undiagnosed/untreated cancer patients; seriously ill patients needing ED facilities etc. Governments cannot allow this to happen so they have to impose restrictions on individual liberties to bring the outbreak under control. In Germany’s case they are responding to their current crisis by contemplating … widespread vaccine mandates!

Vaccination decreases the chance of contracting the disease and transmitting it – thereby reducing the scale of outbreaks. Additionally, because the Pfizer vaccine is highly effective at preventing severe illness requiring hospital care, especially ICU care, it further decreases the chance of the healthcare system being overwhelmed. If the latter occurs the government has no option but to introduce restrictive public health measures (e.g. traffic light red, or worse). If that happens all of society suffers. With highly infectious Covid variants, like the Delta strain, the level of vaccination required to safeguard the healthcare system is well over 90% of the eligible population – every person counts.

I do not think the significance of everyone doing their bit to protect the fragile public health system in NZ can possibly be overstated.

The ledger of benefits vs costs

In the Covid-19 epidemic we are blessed with a range of excellent, reliable, information, e.g. ourworldindata.org, about the public health challenges of this serious disease (> 5 million deaths world-wide so far); of government responses to it; and of the impacts of the latter. The data very clearly show the beneficial impact of vaccinations; and that these beneficial impacts ratchet up dramatically when (eligible) populations are very close to fully vaccinated. The deteriorating situation in Europe reminds us of what could happen here if we are less than completely diligent. So let’s come closer to home and think of the situation in NZ.

Who benefits if someone gets vaccinated?

Here are a few that come to mind:

- Primarily, the person vaccinated: the (age-adjusted) chance of death from a Covid infection is reduced by a factor of 32 (UK Office of National Statistics).

- The friends, whanau and local community of the vaccinated person who have reduced chance of coming into contact with an infected person.

- At risk groups who are not highly protected by vaccination: e.g. aged care residents, immune compromised citizens etc, whose activities have to be curtailed to minimise risk in the event of a significant outbreak.

- Cancer, and other patients with serious illnesses who cannot access timely diagnosis and treatment options if the healthcare system is overwhelmed.

- The healthcare workers, especially in ED and ICU, who have to deal with the consequences of significant outbreaks (e.g. read the harrowing accounts of ICU nurses in the UK during major Covid outbreaks…).

- Children, and others, who can’t get vaccinated.

- The business community who want to minimise the disruption to their businesses by enforced restrictions if an outbreak exceeds the healthcare capacity (e.g. traffic light red).

- Members of the community who want to safely enjoy activities with inter-personal mixing in settings with a high risk of Covid infection, e.g. low ventilation indoor spaces etc.

- Entertainers whose livelihood depends upon the avoidance of large scale outbreaks with the gathering restrictions that flow from that.

What are the costs?

The one demonstrable cost that I am aware of is the question of vaccine side effects. Thanks to the fact that more than a billion doses of the Pfizer vaccine have been delivered worldwide with a high degree of scrutiny by public health officials we know that this vaccine is both safe and effective (with a detailed safety analysis far exceeding that of almost all other pharmaceuticals – clinical trials typically involve a few tens of thousands of volunteers).

Over 99.9% of people vaccinated have, at worst, mild side-effects – perhaps a few hours of a sore arm, headache, or mild lethargy. More severe side effects do occur (often in people who know they are at risk) and are generally much less common than the rates of equivalent symptoms for Covid itself. Without more specific details, I can’t hope to evaluate any other costs that may lead people to underestimate the individual good being given up.

Is government tolerance for MacDonalds a “real contradiction at play”?

With regard to the MacDonalds analogy, I agree that freely distributed Big Macs are a curse on society (although I think it is a push to think that their adverse health impacts are comparable to those of a significant Covid outbreak). As with Covid, the main harm is to the ‘infected’ individual with a residual harm in terms of demands on the health care system down the track. However, the analogy stops there: the public health issues are fundamentally different – to use medical parlance, the problems are chronic rather than acute. The ED and ICU departments are not flooded with Big Mac victims in the days following a MacDonalds opening in a new suburb, they trickle in over decades. I am not sure of the usefulness of such analogies, but if you want one with takeaway food, perhaps NZ’s favourite treat of fried chicken (another takeaway nasty) is a better example: if the chicken is not properly cooked and handled then campylobacter and/or salmonella food poisoning can lead to a rush on hospital care … and we have (food hygiene) laws against that (e.g. a chef in the UK has just been jailed for killing a pensioner with improperly cooked mince)!

So is there hypocrisy here? There is an expectation in modern societies that governments should take reasonable measures to prevent avoidable harm to citizens. Legislation to this effect is manifest in e.g. Health and Safety Laws, Traffic Laws (drink driving limits, speed limits, road junction rules etc), and, indeed, much of our Criminal Justice system. However, in general, governments shy away from legislating against harmful activities which are a personal choice and where the chance of significant harm to others is low. Instead, legislation is aimed, primarily, at behaviours that could cause significant harm to ‘others’ and where there are simple measures that can minimise this harm. For example, most governments, including in NZ, ban smoking in indoor public spaces, but not smoking itself – the health risk of passive smoking is significantly less than active smoking but the burden falls on ‘others’, often against their will). I think that this situation is closer to the Covid vaccination situation than the fast food analogy – especially if you believe (as I do) that vaccination is a simple, safe, measure that decreases the potential harm to the wider community of significant Covid outbreaks.

In conclusion

I agree that in the end, it is up to individuals to balance their own judgement of the benefits and costs and choose what is best based on their personal situation and values – having done everything they can to obtain accurate data to inform that decision. Having done so, they can live with the consequences of their actions.

In making their decision, I think that there is one last thing to be aware of: if the residual concerns are political ones (government over-reach, legislative inconsistencies etc, as implied in some of the critique of Garry’s message) these are reasons to vote for a different government they are NOT reasons to not get vaccinated.

By coincidence, I read an article with a similar title written by immunologist Christopher von Roy a couple of days ago. He is a member of FACT (Fight Against Conspiracy Theories) and his blog gives some excellent information from an immunologist’s perspective. Here’s the link for anyone who’d like to read it: https://christophervonroy.substack.com/p/to-vaxx-or-not-to-vaxx-is-this-really?fbclid=IwAR28VnePMkS7eS-SCfUkJ8aNio1SOGn2PZZbLV64XEtIbAU6pqR7_ZflzXE

thanks Di