A few weeks ago we had the legendary community organiser Vivian Hutchinson at Tuesday Club. Here is his reflection on the visit: Read article in full here

I’M A VISITOR from Taranaki, and I suppose I am here because Garry Moore and I have worked together on many projects over the years. He’s asked me to speak because over the last decade — until Covid intervened — I have been part of running regular community circles in the New Plymouth District Council chambers.

You could say that we in Taranaki have been something of a distant cousin to this Tuesday Club here in Christchurch, especially in our common purpose of hosting conversations between active citizens.

These are my offerings today, which I hope will become part of your conversations to follow.

I want to thank you for organising this regular focus of active citizenship on civic issues. It’s been a privilege to be here. The Tuesday Club is important because it is a forum that adds community intelligence to the issues of our time.

And this public intelligence is the intelligence that needs a conversation for its thoughts to ripen and mature. That’s what’s afoot here.

Masterclass for Active Citizenship

I have also created and convened an award-winning community education programme called the Masterclass for Active Citizenship. This has been done with a team of local people concerned about how active citizenship is an important building block of healthy communities. I’ve also been working closely with local kuia Ngaropi Raumati, who has hosted the Masterclass at Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki, which is a tangata whenua development and liberation service.

I’m pleased you have asked me to speak halfway through your process tonight, because that’s what we also do at our Masterclass. Our own wananga sessions are three hours long, and participants are first invited to share their own keynote speeches on the topic at hand, and then have conversations in small groups.

Ngaropi and I often don’t get to speak until about two hours into our process. This reinforces the fact that the most important thing happening in the Masterclass is not listening to us, but enabling active citizens to have much deeper conversations with one another.

When we do speak, we offer what we have called our “stretch” sessions … because we see our job as elders and conveners as stretching the thinking that is already in the room.

Ngaropi Raumati has also captured her own stretch sessions by recording them on video, and these are available on the Tū Tama Wahine website, under the title Te Kai o te Rangatira.

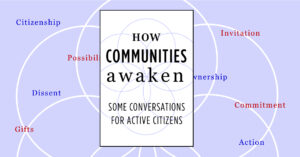

During the Covid months, I took the opportunity to write up what had emerged from my own sessions, and this has turned into a series of essays which have been published under the title How Communities Awaken. They are freely available to read on the Community Taranaki website — you can also easily read them on your mobile phone — and we have produced a gift edition as a book.

Ngaropi Raumati has also captured her own stretch sessions by recording them on video, and these are available on the Tū Tama Wahine website, under the title Te Kai o te Rangatira.

Anyway, Garry has asked me to talk about the community and citizenship themes of my recent writing, and to offer some stretches on the things that have I have been thinking about while I have been here in Christchurch … which could be a pretty wide selection of topics.

But as a rough guide, and to try and keep things short, I thought I would talk about three things: The first is about a piano and a bull. The second is about a woman who is five stories high. And the last one is about a man who gets things done.

The Bull and the Mayors Taskforce for Jobs

YESTERDAY I VISITED the Christchurch Art Gallery with Garry’s wife, Pam Sharpe. After exploring the different exhibitions in the Gallery, I was struck by the Michael Parekōwhai artwork outside on the forecourt. It is a sculpture in bronze and stainless steel of a piano with a bull standing on top of it.

I know its a famous sculpture here in Christchurch, but it was the first time I had seen it. The bull wasn’t charging, but it was certainly full of muscle and aggression. If there had been someone sitting on the piano stool, they would be looking eye-to-eye with a very threatening creature.

Who really knows what this sculpture is all about? Parekōwhai has named it “Chapman’s Homer” which is a reference to a Keats poem, and sounds suitably artistic and esoteric … which means I’ll have to look it up on Google.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that this sculpture has captured the hearts of Christchurch people where it has been seen as a symbol of the resilience of this city in the face of the powerful forces of the earthquake of 2011.

But like any great work of art, we can invest whatever meaning we like onto it, and such meanings do tend to change over time.

When I looked at it, I was reminded of the charging bull that is in the heart of the financial district of New York. That public sculpture is a symbol of a “bull” market, a time that is supposed to bring us financial optimism and economic prosperity.

But looking at this Christchurch bull, I had other feelings.

I remarked to Pam that it reminded me of when I got angry over breakfast that very morning while reading the news. I had been following the reports where the New Zealand Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr was saying that we needed to raise unemployment in order to control inflation.

I was angry because this seemed like a very familiar bull in our national financial affairs. It was a beast that has been plaguing my own work in our communities for decades.

The trade-off between unemployment and managing inflation might seem an esoteric matter of central banking to most of you, but not to me. Garry Moore and I have been working on various community employment projects for over forty years, and this is just the sort of hard-wired economic thinking that our efforts have been continuously up against.

We started the Mayors Taskforce for Jobs when Garry became the Mayor of Christchurch in the late 1990s. It had as its objective that no young person in New Zealand under 25 years would be out of work or training, or having something useful to do in our communities. It was a remarkably refreshing initiative and a national project. Nearly every Mayor in New Zealand —from across the political spectrum — signed up as a member and were engaged on local employment projects and sharing skills and ideas with one another.

I was there as an adviser from the community sector, and my main reason for getting involved was because I no longer wanted to live in a country that had no use for such a large number of its young people. And at that time, we had something like one in every six young people out of work or not connected to any education or training.

Just as an aside, I need to point out that we are the only living creature on the planet that has unemployment as a fact of life for its young. And because this issue is so fundamental to wellbeing in our families and our communities, unemployment has always been at the forefront of our cultural and political lives. And let’s not also forget that one of our two main political parties is named after our ability to work.

But back to the Mayors Taskforce for Jobs. One of our most significant early meetings was when a core group of Mayors met with policy advisers from the Department of Labour. They very kindly sat us down and explained to us the reasons why our goals for the full employment and full participation of our young people could not be achieved.

They explained to us that unemployment was built into the structure of how the national economy was managed. In their view, there was always going to be a trade-off going on between the rate of unemployment and the rate of inflation. This understanding in economic orthodoxy was called the Phillips Curve (named after the theories of a New Zealand economist called Bill Phillips).

The Labour market advisors even have this policy device called the NAIRU, which stands for the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, which gives them the lowest unemployment rate that can be sustained without causing wage growth and inflation to rise.

Having these ideas hard-wired into the algorithms of our economic management can sound like a weird conspiracy theory to anyone not versed in the details of macro-economics. That’s what I thought when I was first introduced to them.

I quite naturally thought: How can you have politicians and bureaucrats going around complaining about people being lazy or unskilled — pointing to their bad attitudes or shoddy work habits — when the sordid truth was that they were planning for these people to be unemployed and “losers” all along. From a family and community point of view, it seemed — and frankly still seems — crazy.

The core group of Mayors saw the role of the Taskforce for Jobs at that time as standing for the community goals of full employment and full participation. Nobody puts themselves forward to be Mayor of any place that has already decided that it has no use for a substantial number of its own young people. The Taskforce described its goals as “cultural goals” because we wanted a “zero-waste” of people in our own communities … and we frankly expected the Reserve Bank and our national politicians to be our allies and collaborators in making these cultural goals happen.

What happened to the Mayors Taskforce is a story for another time. It is still going, and it is still doing good work. But I will let you judge for yourself whether it is also still seriously advocating for the “cultural goals” which have not stopped being relevant today.

( Economists now have this thing called the NEET rate, which measures the proportion of young people aged 15-24 years who are not employed or engaged in education or training. Even at this time when the official unemployment rate is statistically quite low, the NEET rate here in New Zealand is still hovering around one in every seven young people. )

But back to the Art Gallery, and the sculpture of the bull and the piano … it had stirred feelings in me as I was also thinking about that Reserve Bank statement.

I saw the piano as representing all the things that we value in our communities because it is an instrument capable of much beauty and celebration. But we will never to get to the music if we don’t sit on that piano stool and face down that bull. If we don’t step up and stand up for the things we value in our communities — facing all the power and threat and aggression that the bull represents — then the piano stool will always remain empty, and it will also remain an indictment on all of us.

I do think we are going to look back at this time in our history and recognise that it will become as consequential to the wellbeing of our communities as the 1984 reforms were for the 4th Labour Government. You might not immediately recognise it as such, but that is because the algorithms driving these consequences are hidden in the macroeconomics of our financial decisions.

The financial journalist Bernard Hickey is an excellent explainer of what’s going on. He has spoken to this Tuesday Club over the last year, where he detailed the huge shifts of wealth that have happened since the onset of Covid. He describes it as happening “accidentally on purpose”, which I suppose is what takes place when there’s no-one sitting at the piano, and you just leave it to the algorithms.

Bernard Hickey reports that the Government and Reserve Bank have presided over policies which have helped make the owners of homes and businesses $952 billion richer since December 2019. The Covid years have seen what Hickey calls “the biggest transfer of wealth to asset owners from current and future renters in the history of New Zealand.”

Meanwhile, those New Zealanders who have missed out on that asset growth have been hammered with real wage deflation and rents rising faster than incomes. The poorest New Zealanders are now $400 million more in debt and need twice as many food parcels as before Covid.

That’s stunning. And it’s not the economics of community. It is certainly not an economics that reflects the best intentions of a “team of five million” which, you’ll remember, is how we branded ourselves in the early days of the pandemic.

For some of us, it is heart-breaking that this dramatic shift in wealth has happened under a Labour Government, supported by the Greens. For those of us who remember the 1980s, there is a definite sense of déjà vu.

You can only imagine what community workers in Taranaki like myself were thinking when Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern turned up recently and spoke to her party caucus at a rural retreat near New Plymouth.

There she announced that her government had managed “equity and fairness” with “Labour values” during the Covid crisis, and would continue to “manage challenges and change when it comes to climate, housing, poverty, everything we continue to face as a nation.”

It’s the right words, for sure, and certainly what we want to hear as a “team of five million”. And I’m not saying that our Prime Minister is a hypocrite. What I am saying is that if she looks across the road, she would see that the bull is no longer in the paddock.

Hana Te Hemara (1940-1999)

IN THIS SECOND PART, I want to invite you to Taranaki and talk about another artwork which has just been unveiled in New Plymouth’s CBD. It is a five-stories-high mural on the back of our Puke Ariki Library building and it celebrates the radical activism and creative work of Hana Te Hemara, or Hana Jackson.

Hana Te Hemara (1940-1999) was of Te Atiawa descent, and born at Puketapu, near New Plymouth. She is well known as one of the dynamic founders of the activist group Ngā Tamatoa which demonstrated and organised around many important issues, including the revival of the Māori language. Their activism paved the way for the thriving kura kaupapa, kōhanga reo and te reo Māori movement we have in Aotearoa today.

Hana herself was a leader in many other ground-breaking initiatives. She helped Hone Tuwhare set up the first Māori Artists and Writers’ Conference, and she also later established the first Māori Business and Professional Association. She was a gifted fashion designer, and organised the first Māori fashion award, and the fashion shows which ran in conjunction with the Te Māori exhibitions.

Hana died quite young at aged 59, yet I think there are many of us who feel that she has left a tremendous legacy for future generations. So it is wonderful to see her being celebrated on our Library building.

The mural is the work of prominent Māori artist Mr.G Hoete, and it was commissioned to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 14th September 1972. This was the day when Hana and Ngā Tamatoa walked up the steps of Parliament to deliver a petition calling for an official programme of support for the Māori language, and for getting Māori taught in our education system. Because of this petition, the 14th of September later became known as Māori Language Day, and eventually, the beginning of Māori Language Week.

The celebrations of this anniversary were led by Hana’s family and by Te Atiawa and there was also strong support from our local District Council. The Council not only approved the mural being on our local Library building, but ran banners around town proclaiming I Am Hana, and hosted a street party to celebrate the unveiling of the finished artwork.

Many of the Ngā Tamatoa activists, now in their 70s and 80s, were welcomed to New Plymouth and there were also public forums and a photo exhibition celebrating their work.

These anniversary celebrations were open-hearted, good natured, and almost completely without any polarising controversy. You might think that is unusual for Taranaki, given that we have gained a reputation on some contentious issues over the last decade, especially when trying to get more Māori voices around the District Council table.

And I feel I need to point out that this is the same District Council, under the same Mayor, that only four years ago fought for enabling legislation to be passed which succeeded in privatising the last of the stolen lands of Waitara.

These lands, known as the Pekapeka Block, were at the heart of the war that broke out at Waitara in the 1860s, and then spread to the rest of Taranaki. These are the lands that have represented a very long story of blood and dishonour connected to the original sin of our nation — the confiscation of Māori land upon which has been the foundation of so many of our towns and communities.

The introduction of the Waitara Lands Bill represented an opportunity for our generation to begin to really heal and address this injustice. It was an opportunity not taken. The Waitara Lands Bill was passed by the incoming Labour-led government and, since then, the District Council has sold many of the properties.

I knew Hana well, and I believe that, had she still been alive today, she would have been one of the leading voices in the fight to get these still-disputed lands restored to their rightful owners, the hapu of Waitara.

So you may imagine some of the complicated feelings brought up by my District Council choosing to celebrate this radical activist and the 50 years since the presentation of the Māori Language petition.

But it is important to recognise that some significant things have indeed shifted in just the last four years — and shifted in ways that perhaps we were not expecting. ( … this hasn’t happened in terms of the Waitara land issues … but that’s not a story that has finished yet).

I do think there have been important shifts that matter in terms of relationship-building. And there’s a new generation coming through that are just side-stepping the historical stuckness, and expecting things to be different, and they are getting on with it.

We have Māori Wards now throughout our district. We have a new generation of Māori leaders emerging who are taking their place not just around council tables, but in board rooms as well in lawyers offices, as accountants and as entrepreneurs.

I’ve noticed more people of all ages signing up to learn te reo, and to try and better understand the world view of Māori communities.

I’ve noticed a full embrace of the new and indigenous public holiday of Matariki and how this has immediately enabled us all to look up, and view our world within a profoundly wider story.

All these things are inevitably changing the character of our place.

So when I saw the I Am Hana banners flying around New Plymouth, I felt that yet another building-block of peace and reconciliation was trying to do its work in our city. The civic embrace of this 50-year anniversary was not just something we could all welcome … but it was being done in such a way that we could genuinely appreciate this daughter of Taranaki as one of our many role models for future generations.

I seem to be continuously reminded that change often happens in ways that we least expect it, and in a time-frame that is seldom under our choosing. At the same time, I am also reminded that the responsibility of a community builder is to keep shaping those assets which are the building-blocks of peace and reconciliation, and can lead to the possibilities of change.

Hana and I were on the organising committee of the Māori Land March of 1975, and she knew well — as Whina Cooper and the other members of Te Roopu o te Matakite also knew — that the loss of land and the loss of te reo are inextricably interrelated.

So when it came to setting a date for the Māori Land March to begin, it was Hana who pushed for it to start on the 14th of September — the same day that Ngā Tamatoa walked up the steps of Parliament to present their petition for the protection and restoration of the Māori language.

Hana herself was not a fluent speaker of te reo. So her motivation for walking up those steps was deeply personal. She was determined that her own children and grandchildren were not going to suffer the same fundamental sense of loss.

Learning a language as an adult is no easy undertaking. I am Pākehā, and yet despite a lifetime in Māori company, my own proficiency in the Māori language has not really improved very much from the limited level that I had in the 1970s. I do get by on ceremonial occasions, but I honestly get quite lost in a deeper dialogue. I have found that without the senses that awaken within a fuller immersion, the academic learning of another language as an adult has not turned out to be one of my talents.

Nevertheless, I have been reflecting lately on how I have spent the currency of my life trying to preserve and regenerate some of the other languages which have also been under a constant threat of their marginalisation and extinction.

These have been the languages of community, the literacy of the commons, and a working vocabulary of what is expected from our citizenship at this critical time.

These languages underpin our common sense of how we can work together on the things that matter. They are complex and dynamic. They are also not easy to learn. But without these languages, and without the practical living skills that they articulate, then we just degenerate into a political and cultural morass of self-interest, toxic individualism and “me-first” economics.

I believe the language of community has been under sustained assault over the last forty years. Consequently, the voices and passions of the commons have become more and more inarticulate, or they have completely disappeared from the public discourse. As this has happened, we have lost a huge amount of the breadth and depth of shared meaning and understanding — and just the plain beauty — that is wrapped up in a community-centered way of looking at our lives and our world.

This is one of the reasons why I started the Masterclass for Active Citizenship. It is a local and modest example of reclaiming that beauty, and of regenerating that community voice.

And when I look at the new mural on the back of our Library building, I recognise that we can learn a lot from Hana Te Hemara and the last 50 years of advocacy for the recognition and support of the Māori language. Because the fight is similar: it is not just about vocabulary lists of words-in-translation, but about the validity and honesty of an entire way of seeing and explaining the world.

The core strategy of our Masterclass is about slowly regenerating the shared language of community — one relationship at a time, one story at a time, and one building-block at a time. And over time, the health of community begins to piece itself together again, and we start to re-awaken the unique work that communities need to do.

We have only had about four hundred people go through our 3-4 month course, but it has already amounted to the most effective community development strategy that I have ever been involved in. Virtually every marae, church group, service club, and even some sports clubs in Taranaki, have had people come along and participate.

And we often hear people make comments like: “I feel more like myself than I have in a long time…” or “I do remember thinking like this … what happened? Why did we let this go?”

The answer to that “Why?” is a subject worthy of much more consideration. If our public institutions, our communities and our personal lives have become so successfully colonised by world-views that are serving goals other than our collective health and wellbeing … then it is important to figure out how this happened.

In the meantime, it is up to community workers to make sure that every event we organise is seen as an opportunity to rebuild our social technologies, and to stress-test and maintain our infrastructure of public intelligence.

Just like the regeneration of te reo, our efforts to regenerate community may take two or three generations before we really start to see its fruits.

This is work we do with all our children and grandchildren in mind.

Beware the politician who is asking nothing of you.

Beware of the confidence of politicians that are telling you to leave them to it, and they will manage the disruptions, and keep all the threats in the paddock. Beware the man who says he will will get the job done.

We’ve just had the local government elections and — let’s face it — the progressive voices of community were not the winners. I’m not here to dissect and debate the results, but I do want to draw attention to the character of some of the main messages I have been hearing during this election time.

In the Mayoral elections both here in Christchurch, and also in Auckland, the winners were men who were campaigning under the slogans of “I’ll get it done”, or “I’ll fix it” … as if the main source of our collective problems is absence of anyone who has the strength and willpower to face them.

It reminds me a little of Boris Johnson in the UK campaigning (and winning a decisive majority) under the slogan of “I’ll get Brexit done”, or the former American President Trump when he said he would build a wall on his southern border, and get Mexico to pay for it.

This sort of branding and marketing is simplistic, yet obviously effective. You can’t really argue with “the action man”, or the idea of fixing things, especially when things are also so obviously stuck or broken.

But there’s a warning here, and this is that the action man has often proven to be playing a shell game or a confidence trick with the voting public. Sooner-or-later we have to wake up to it.

You only need to look at the shemozzle happening in UK politics in the last few weeks to see that the emperors have no clothes, and even the financial markets are no longer going along with it.

One of the reasons the “I will get it done” message is so effective is that it rests upon the general story-telling in our culture that portrays the business-person as our saviour. We are willing participants in this confidence trick, because we have a definite hero-worship going on for the can-do entrepreneur.

The hero-worship has come at a cost, because these confident stories of business and entrepreneurship often end up diminishing of the very idea of public service, and the harder work of consensus-building.

And when we are seduced by business culture, we end up looking for the same answers from the same old toolbox.

Look at some of the big public issues facing our nation at this moment: the state of our health system, or the polytechs, or the maintenance of council assets (… now commodified and rebranded as “three waters”).

The answer always seems to be the same. Run them like a business. Reorganise and restructure them into bigger entities. Appoint new bosses (at salaries that match the private sector). Then double-down on the same management strategies, even if they may have led to our problems in the first place.

Again, the missing element here is the intelligence and wisdom of the citizens and communities that these public entities were meant to be serving. Our communities are the asset that is right under your nose, yet ordinary citizens have not been invited to the table.

So when it comes to “getting the job done”, I want us to notice that the “job” itself has essentially changed. Business-as-usual is no longer making sense.

We need a political and cultural leadership that doesn’t say “I’m going to fix it” … as if all the rest of us can just sit back and be spectators and commentators, but essentially just leave you to it.

If you are a candidate for public office, your role now is to stop offering a consumer transaction with voters, and start directly asking for their participation.

We need to be electing people who are capable of turning the usual leadership story on its head. This is the leadership that looks the voter in the eye and says: “I need you to awaken. I need you to be as grown-up a citizen as is possible. Because every one of the big problems we are facing right now needs your engaged citizenship.”

And this form of leadership is not a job of branding and marketing in the context of retail politics. It is a job of invitation, and of connection.

And you may be surprised at just how many people are waiting to be authentically asked.

So my stretch is this: Beware the politician who is asking nothing of you.

Beware of the confidence of politicians that are telling you to leave them to it, and they will manage the disruptions, and keep all the threats in the paddock.

Be especially aware of the politician who is quite happy for you to be disconnected and disengaged at this critical time, and claim their own legitimacy while a third of the electorate are not even turning up to vote.

Instead, look towards the politicians who are capable of calling you to the commitments and responsibilities of your active citizenship … which is both the necessary ask of this moment, and the necessary ingredient to solving so many of the complex problems that are before us.

Look towards to the politicians who already know that “we” is not a small word, and that they have a specific role to play in making sure that “we” will get things done.

Our human capacity to think and create and respond together has been the real source of our species talent for hundreds of thousands of years.

We need these talents right now, and the job description of all our leadership is to call these talents forward.

Leave a Reply